| View previous topic :: View next topic |

| Author |

Message |

faceless

admin

Joined: 25 Apr 2006

|

Posted: Sun May 20, 2007 5:03 pm Post subject: Paul Merton Posted: Sun May 20, 2007 5:03 pm Post subject: Paul Merton |

|

|

|

|

Great Paul in China

19/05/2007

Great Paul in China

19/05/2007

Paul Merton tells Andrew Pettie about the foibles and fascination of China.

www.telegraph.co.uk

Paul Merton is in a minibus bound for the Great Wall of China. He’s in the process of filming Paul Merton in China (Five), a new four-part travelogue in which he criss-crosses the country in search of the engaging and the extraordinary. You might think that the Great Wall – which at over 4,000 miles is the longest man-made structure in the world (although it’s not, as popular myth would have it, visible from space) – falls into both categories. His Chinese guides are certainly looking forward to showing it off. Merton, however, has other ideas.

‘I’m not really interested in the Great Wall of China,’ he announces matter-of-factly in the opening episode. ‘I was reading today’s paper and there’s an article here about a farmer, a Mr Wu, who grows robots. Now that sounds fun, doesn’t it?’ And so maps are hastily consulted, schedules scrapped and the minibus pointed in the direction of Mr Wu. Two hours later Merton is interviewing the proud creator of a robot-drawn rickshaw, giggling with enthusiasm at his ingenious but pointless inventions.

Back in the UK and reflecting on the highlights of his six-week trip, Merton still sounds a little obsessed with the robots. ‘Mr Wu also showed me a mechanical table he’d constructed,’ he laughs. ‘It served no purpose at all apart from the sheer fun of building a walking table. You couldn’t put anything on it without it being spilt. And it didn’t even have the advantage of being a fast table. It would take half an hour to move three yards.’

This entire escapade, in which Merton foregoes one of the wonders of the world in favour of meeting the inventor of a walking table, sums up his methods as a tour guide and, indeed, as a comedian. He can seldom be bothered with the straightforward, preferring, if possible, to make a beeline for the surreal. In the first instalment alone he samples fried donkey’s penis (‘Well, I can tell he wasn’t Jewish’), then hijacks a karaoke party held at a faux 17th-century French chateau by singing Unchained Melody in his dressing gown. Beneath the daft facade, however, Merton has clearly done his homework.

He tells us that, remarkably, there has been more construction in China in the past year than there has been on the whole of continental Europe for the past three. He shows us Shanghai, ‘a city on steroids’, where houses are being bulldozed to make way for showy skyscrapers too expensive for any Chinese citizens or businesses to afford. These impressive buildings will, reckons Merton, remain empty indefinitely. He grapples with official censorship (‘We had a Communist minder with us all the time, then three minders when we visited Tibet’) and is quick to probe his interviewees’ reluctance to be entirely candid on camera.

‘At one point we’re in a very polluted city,’ he remembers, ‘talking to a highly-educated resident. “How do you deal with the pollution?” I ask. “Oh, I don’t think it’s polluted,” she says, quite seriously, “I think it’s fine.” Yet when we look up there’s so much smog in the air it’s possible to look directly at the sun. Chinese people, you see, don’t want to be caught saying anything that could be interpreted as a criticism of the government.’

Thankfully, Merton’s excellence in his new role as a wisecracking Alan Whicker will not distract him from his day job – which, for the past 17 years, has been as the Hislop-bashing team captain on Have I Got News for You. He says he’s happy to appear on the show ‘till death… and beyond!’ and thinks that the introduction of guest hosts has been a tonic. ‘Freshness is now built in,’ he says. ‘Plus some of the regulars are getting very good at it.’ Boris Johnson is a favourite. ‘Boris is that charming mixture of the intentional and the unintentional,’ Merton chuckles. ‘But he has a carefully cultivated public image. I’ve seen him leave make-up with his hair perfectly combed, then within 30 seconds he’s put a hand through it to create that ruffled look.’

Merton’s one great unfulfilled ambition is to write and direct a feature-length comedy (‘I have a draft idea that I’m working on’). But before that project can take shape he has to finish his new book, Paul Merton’s Silent Comedy, a detailed study of one of his passions and the subject of his fine 2006 BBC4 series Silent Clowns.

‘I’ve got 60,000 words to write of which I’ve only done about 40 – 40,000, that is, not 40 full stop. It’s already up on the Amazon website. In fact I’ve preordered a copy before I’ve even got round to writing it. What a terrifying thought.’

# 'Paul Merton in China'is on Five on Monday at 9.00pm

-----------------

Sounds pretty interesting - I've always liked his style and I'm sure this will be good. I'll try and cap it if there's nothing else on... |

|

| Back to top |

|

|

faceless

admin

Joined: 25 Apr 2006

|

Posted: Sun May 27, 2007 3:19 pm Post subject: Posted: Sun May 27, 2007 3:19 pm Post subject: |

|

|

|

|

'I didn't go to a dinner party until I was in my thirties'

Brought up on a diet of fish fingers, Pot Noodles and porridge, Paul Merton's idea of a culinary adventure was a night in with a Vespa curry. But then he went to Beijing - where eating on Dog Street was the least of his challenges ...

Interview by Vincent Graff

'I didn't go to a dinner party until I was in my thirties'

Brought up on a diet of fish fingers, Pot Noodles and porridge, Paul Merton's idea of a culinary adventure was a night in with a Vespa curry. But then he went to Beijing - where eating on Dog Street was the least of his challenges ...

Interview by Vincent Graff

Sunday May 27, 2007

The Observer

I am talking penises with Paul Merton. He's telling me about the evening he spent recently in the company of a donkey's giant genitals. No need. I've already seen the evidence. It was a huge brown thing as long as your forearm and presented to him roasted on a bed of cucumber and decorative orchids. Then it was whisked away, delicately spiced and sliced, and served up in a creamy, bubbling soup. Finally Merton put it in his mouth.

You'll be wanting to know - did he spit or swallow? The answer is that, after chewing for a few seconds, Merton ate the donkey penis, wincing only slightly. 'Mmm, that's good,' he said politely. Then, less politely: 'When I say it's good, I've no intention of ever eating it again in my life.'

Merton had been taken to a Beijing restaurant that specialises in penis cuisine. As you'll already know if you saw the first instalment of Paul Merton in China on Channel Five on Monday, he also sampled the testicles and forked penis of a snake and a sheep's penis that had 'the texture of knotted rope'. It was the latter that beat him.

'The donkey was all right,' he recalls. 'If you hadn't known what it was, and it was just slices on a plate, you could have mistaken it for lamb or beef. It was not a flavour I was familiar with but it was in that kind of area. But the sheep one was so intensely chewy, there was no taste in it and the texture was just horrible.' He spat it out. It was, in the words of Merton in the programme, a case of 'too many cocks spoil the broth'.

Food is a recurring theme in the four-part travelogue documentary. For the record, he turned his nose up at the idea of eating cicada, scorpion, sheep penis and dog but was happy to swallow donkey penis, snake penis and an inventive nomadic Tibetan dish that involves cooking lamb in its own stomach without the use of any stove or oven (the trick is to include red hot stones as part of the stuffing and to sew the stomach up). All rather more daring than the dim sum we're eating at Shanghai Blues, one of Merton's favourite Chinese restaurants, in London's Holborn.

If Merton, 50 this year, is now a relatively adventurous eater, this is a new departure. As we shall discover, he was not someone who grew up with a love of food. For six years, he lived on his own in depressing bedsits with almost no cooking facilities (he lived in one that only had a kettle). He was in his twenties before he learnt that people put their knife and fork side by side to signify that they have finished eating, and he had never been to a dinner party until he was married and in his thirties. Yet today he avoids too much gluten in his diet and believes in the power of 'superfood' vegetables to fight disease.

Meanwhile, back to China. The documentary - an entertaining attempt to make sense of a nation transforming itself from a third-world country to a superpower-in-waiting - contains a fascinating scene where Merton and his camera crew visit an area that specialises in restaurants serving dog meat. To film the sequence, Merton and his cameraman posed as holidaymakers. Diners, delighted and amazed to see European visitors to Dog Street, as the area is colloquially known, smiled and waved, merrily pointing to the food on their plates. 'They didn't know we were a Western film crew because we had a very small camera that looked like it might have been a home movie thing,' explains Merton.

If the restaurant-goers were pleased to see him, the Chinese government won't be. Merton's team had been refused permission to visit Dog Street and he went behind the back of the official minder who'd been assigned to accompany him for his six-week trek across the country.

'They didn't want us to go there because they didn't want us to put over that old-fashioned idea of China. But it's not an old-fashioned idea, because dog is a famine cuisine - there's a saying that the only thing with four legs that the Chinese won't eat is a table.' He is filmed discussing the issue with an obviously educated woman who speaks perfect English. 'And she did not know the phrase "pet dog". In a culture where you haven't got much food why would you have an animal that you have to keep alive with the food you could be eating?'

This time around, once seated at his table, Merton's bravery deserted him. He refused a mouthful of fried 'brown dog' - no one could tell him quite what breed he'd been served up - when the dish arrived. Now that he's had time to think through his decision, I ask him why someone who can swallow donkey penis suddenly came over squeamish.

A little earlier that day, he says, he'd filmed a sequence about how women from China's newly emerging middle class spend their new-found wealth by pampering their (ludicrously pompadoured) poodles. Eating what was on his plate for dinner 'might have been a little bit easier if I hadn't been walking dogs that day'. So he doesn't think eating such meat is inherently wrong, then? Not for a people in their circumstances, no: 'I'm not a vegetarian so it'd be hypocritical to go on as if dogs are in any way different to cows or sheep. A piece of meat is a piece of meat in many respects. I wasn't trying to impose my standards on them.'

So if a dog restaurant opened up tomorrow in Streatham? 'It wouldn't bother me that other people eat dog. It's up to them.' Then another reason for his on-screen refusal begins to emerge. 'There's also the practical side,' he says. 'If you start eating dog on TV you get very angry letters from people.'

So that was part of the calculation - that there may be a campaign against you if you're seen eating one of Lassie's friends? 'Well, maybe,' he says, sounding unsure. He smiles. 'By talking about this I don't want to be targeted as the man who nearly ate dog. Nearly is the key thing.' Big laugh. 'I know how people feel about it - some British people are completely potty about animals, they place them above human beings, so I really don't want to start tangling with people who ...' he hunts for the right words, 'may not have my best health as their number-one priority. I think you know what I am saying.' I do. It's time to move on.

Merton, the son of a Tube train driver and an NHS nurse, grew up as Paul Martin (the name change came later, when he wanted to join Equity) in Robert Owen House, a low-rise block of council flats in Fulham. It was a church-going Catholic household: every Sunday there was a wafer at communion and a traditional roast afterwards. But much of the food served up by Merton's mother in the Fifties and Sixties was drab - and often from the freezer compartment of the fridge. There is no sense of Merton, now a multimillionaire of course, looking down his nose when he describes what his mother gave the family, but equally no attempt to romanticise a diet that appears pretty unappealing from this distance - and didn't do a great deal to excite him back then.

'The food wasn't adventurous,' he says. This was food as fuel, not a source of pleasure. 'First of all, lunch was called dinner and dinner was called tea,' he says. 'I remember fish fingers, rissoles - stuff that Bird's Eye started to sell in the late Fifties, all that instant food. Something out of a packet. I remember when the Vesta curry came out - my first awareness of it was sometime in the mid-Sixties. That seemed extremely exotic.'

Schoolfriends never came round for food - nor did any of his parents' pals. 'Nobody ever came to our place to eat and we never went to anybody else's house to eat. You wouldn't think of doing it. People would have thought: "Why would we come to you to eat? Are you saying we don't have good food at our house?"'. Such thinking may also be 'tied in with the fact that the food wasn't particularly good, so why would we invite people round to have potatoes, peas and meat pie when that's probably what they're having anyway?'

The sentiment has, to some extent, stuck with him all these years later. Does he ever throw dinner parties now? 'No, I don't. This goes back to a class thing.' Instead, he'll invite friends round to his house for a game of snooker or to watch a film. The first dinner party he went to was 'probably when I hosted them, when I was married to Caroline [Quentin]. She is solidly middle class. I must have been 34 or 35.'

People will look at the quick-witted urbane performer on television and be amazed that he was such a late (and reluctant) arrival at the dinner-party scene.

'The class thing is interesting. I'm not sure I'm not middle class - though I'm not sure I am - but equally the working-class stuff hasn't just disappeared. It's there in your background, how you are and how you relax. I went to a BBC dinner party a few years ago which was thrown by John Birt when he was BBC director general and he did this thing where, after each course, you get up and move along a place.'

There's something similar that sometimes happens at Oxbridge high table, I say.

'Oh, like passing the port to the left? All these rules that you don't know. Even simple things like, in the early days of going into restaurants, not knowing that the knife and fork together is a signal that says "take away my plate".'

You didn't know that?

'No.'

You didn't do that at home?

'No. You just left them there. You saw the plate was empty. I'd never heard of the notion that putting the two together to signify that you have finished.'

When Merton found out, he 'wasn't embarrassed about the fact that I didn't know but I thought, "That sounds like a good idea".' So at what stage did he discover the knife and fork trick? 'When I first started going into restaurants. I don't want to make myself sound like a complete ignoramus but I was probably in my twenties. Seriously. I know it probably seems really retarded but I never went into that world.'

Again, this gap in his knowledge is likely to surprise people, I suggest.

'I suppose so. It's one of those quirks. It's one of those things that working-class people don't necessarily know. It doesn't come into the area of manners, does it? We understand manners, we know that you don't sit with your elbows on the table, you don't spit, that's obvious. But you can be from a working-class background and not know the etiquette of putting your knife and fork together because nobody ever talks about it.'

The gap in knowledge is also likely to be another product of the fact that it is only since he has had money that Merton has allowed food to become a source of pleasure. He says: 'I can remember thinking when I was about 19 or 20 that food was a bit of a boring thing that you just had to do to keep going. And if you could've taken a little tablet - as, you know, the astronauts will have one day - to fill you up, I would have gone for that method.'

By that time, Merton had a steady but uninspiring job as a civil servant. He'd wanted to be a comedian since he was a child, and realised that his career, such as it was, at the Tooting employment office had left him wishing his life away.

'I know what it's like getting up on a Monday morning, walking in through the office door at five to nine, looking up at the clock and thinking: "The next time I look at you with a sense of satisfaction it'll be five o'clock on Friday."'

So he chucked his job in. He gave himself a five-year 'apprenticeship' to make it in showbusiness. But the lack of money meant he had to move into a single rented room. It was 1982 - and Merton was to remain in bedsitland until just two years before he joined Have I Got News For You and achieved fame.

'I was in bedsits from early 1982 through to 1988, I think. A long time. At first, I was earning virtually no money. I was signing on, doing occasional gigs for maybe £20 each. I did 15 or 20 gigs in that first year.

'In the first bedsit, I had no facilities at all. The only thing I had to cook with was an electric kettle. So I would make porridge by pouring hot water onto a bowl of oats. If you haven't got much money, porridge is one of the cheapest and best things you can eat because it keeps you going, gives you energy.' If he was feeling a little less virtuous, Pot Noodles - still relatively new - were another food source. Or, 'I'd go to the supermarket and buy a loaf of Mother's Pride bread, which I think was something like 25p at the time, and a pot of fish paste and eat that. Or a bit of Bovril, something with a bit of flavour to it.'

If you think this makes him sound miserable, you've got it wrong, he says - and not merely because he managed to escape (and in some style: he has homes in Islington and Sussex). 'This isn't a hard-luck story and I don't want it to sound like one, because I was freeing myself up to write stuff and pursue a career in comedy.'

As a child, he'd often retreat to his bedroom to listen to his records, 'so as to be in one room on my own wasn't a massive culture shock for me'. The loneliness was 'kind of what I was used to - being sent to Coventry at school, not really having lots of friends. I know I won't have to, but I could go back to that environment again.'

Reading these words on paper, this sounds a little morose. But that is not at all the sense in which it was delivered. Though Merton does not, thank God, feel the need to pep up each turn of the conversation with a wisecrack, lunch with him is a jolly and enjoyable affair. It involves a lot of laughter - there's a little of Sid James in Merton's cackle. And he seems proud to have been a 'bedsit boy', a phrase he uses several times about himself. 'I think success and happiness in life is about contrast in many ways,' he explains.

His life has certainly dished up those contrasts. Four years ago, he had to deal with a very cruel blow. His second wife, Sarah, died in his arms. She'd been suffering from breast cancer.

They approached her illness together and with a belief in the healing effects of diet (albeit working alongside conventional drugs). A few months before Sarah died, he told an interviewer: 'We juice two kilograms of carrots every day - they are exceptionally good for the immune system and very versatile: carrot and apple is beautiful, carrot and pineapple is wonderful ... There are things you can do: diet, mental attitude, spiritual attitude, all these things are very important.'

Today, despite the loss of his wife, he sticks by that conviction. 'You get that terrible diagnosis, the prognosis. So what can you do? Well, a large percentage of cancers are caused by poor diet - it's not just smoking and asbestos and stress - so you look to do things that can boost the immune system as much as possible. Standard doctors don't know anything about nutrition, so some of them tend to pooh-pooh this sort of thing as faddy diets. But the truth of the matter is that if you're juicing a lot, OK it's not going to cure the cancer, but you feel great. And you want to help your body as much as possible.

'I'm completely different to how I was when I was 19. Now I seek out purple sprouting broccoli' - he utters the words as if they are obscure Latin labels in a medical textbook - 'it's fantastically good stuff. And it's tasty as well. You look at what the superfoods are - cauliflower, broccoli - these things have been shown to fight cancer, or at least to help your immune system build up an immunity to it. And we know that if we eat really good food we feel great. If we eat chips, we feel sluggish.'

Yet that new respect for food and his enjoyment of it cannot entirely rub out the effects of all those years that taught him that spending time in the kitchen was anything but a pleasure.

He reflects on where he is today. 'I'm not living in a bedsit, and I've got more than 21p to spend on bread and fish-paste sandwiches, but I still don't cook at home. I've got very little cooking equipment. But,' he adds, 'there are hundreds of restaurants nearby. If you've got £50 in your pocket, you can go into a restaurant and have lunch, so I do that.'

· Paul Merton in China continues tomorrow on C5. Shanghai Blues, High Holborn, London WC1, 020 7404 1668, www.shanghaiblues.co.uk |

|

| Back to top |

|

|

GingerTruck

Joined: 19 May 2007

Location: tipton west midlands uk

|

Posted: Sun May 27, 2007 10:45 pm Post subject: Posted: Sun May 27, 2007 10:45 pm Post subject: |

|

|

|

|

| this was a great show and i am looking forward to the rest it is great to learn about different cultures even if you dont always agree with them |

|

| Back to top |

|

|

faceless

admin

Joined: 25 Apr 2006

|

Posted: Thu Oct 25, 2007 4:54 pm Post subject: Posted: Thu Oct 25, 2007 4:54 pm Post subject: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Back to top |

|

|

faceless

admin

Joined: 25 Apr 2006

|

Posted: Fri Jun 13, 2008 12:42 am Post subject: Posted: Fri Jun 13, 2008 12:42 am Post subject: |

|

|

|

|

In a showbusiness world where gossip, conjecture, rumour and tittle-tattle can often reign supreme, Paul Merton may think himself lucky to have got off relatively lightly. The most savage bit of whisper mongering he has encountered in recent years was the scandalous claims from one tabloid that he and Noel Edmonds were going head-to-head for the Countdown chair.

“It’s true that I was asked if I wanted to audition for it but I said no and then this piece appeared,” the comedian says. “I was amused by the notion and flattered by it, but the reality of that show is that they record five [shows] a day for three weeks and then you have a whole series for six months or whatever it is. The people who watch and play the game take it very seriously. Even if you could think of gags in the course of three weeks for six months of programming, you couldn’t think of enough and the people who watch it don’t want gags, they just want the quiz.’

I feel slightly guilty telling Merton that I have come from Edinburgh to meet him, as two sour experiences of the famous Fringe festival still live vividly in his memory. In 1986, he was attacked while helping put up a friend’s poster and the following year he found himself in a hospital bed after breaking a leg during a comedians’ football game, eventually contracting Hepatitis A.

The reviews had been kind to him at that point but his premature Fringe burial meant taking a financial hit which he found tough to recover from. He can just about see the funny side of such incidents now, which is fortunate as Merton has an appealing laugh. At one point along its trajectory, it’s hearty, while at its extreme end it’s almost bellowing. Not at anything that I have to say, mind you, but of the daft things he’s encountered down his near three decades in the comedy business.

Such as recalling one of the inspirations for his own early stand-up, Alexei Sayle, Merton saw him perform at London’s Raymond Revue Bar at the dawn of the 1980s, with his tight suit on and his hat down over his eyes, “doing this extraordinary thing he called the stream of tastelessness which was every single swear word you could think of just put into a sentence without any other words at all and getting faster and faster with this aggression and his Scouse attitude. It was hilarious.” With perfectly valid reasons, people find Paul Merton hilarious.

After our interview, something to eat and a quick nap, Paul is off to record more of Have I Got News For You’s 35th series. Even those who have had their fill of the long-running news quiz concede that the bamboozled surrealist shtick that Paul has cultivated to utter perfection is still enough to make them tune in from time-to-time.

Meanwhile, hardcore fans will get all dewy-eyed when dragging up recollections of his Channel 4 affair Paul Merton: The Series, a sketch show which lasted two seasons in 1991 and 1993 and in that Fast Show/Newman & Baddiel era of the sketch show catchphrase, the closest Merton got to his words rattling around the schoolyards or offices of the nation were “innit marvellous?” the concluding remark uttered by his only regular character who, were this The Simpsons, would be called Newspaper Kiosk Guy.

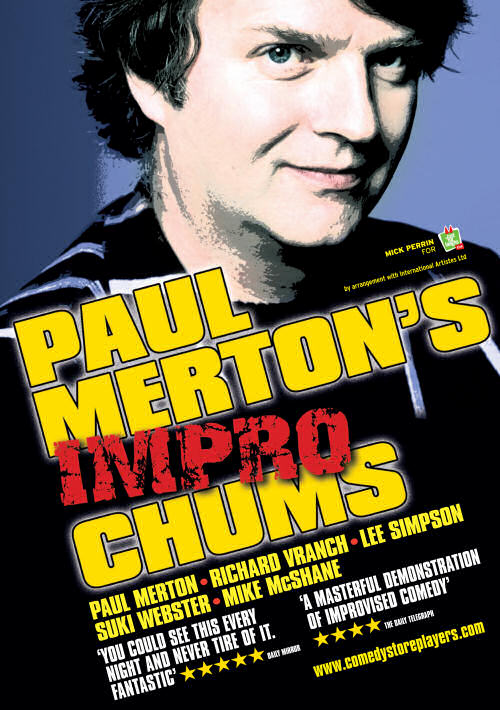

Paul is today in his management company’s office in Central London to chat about his latest venture, as he goes back on the road with his Impro Chums. Although Merton’s face fills the poster and the show title reminds us that we can spend time with Paul’s pals, he is never less than gracious when talking about his fellow ad libbing colleagues – Suki Webster, Richard Vranch, Lee Simpson and Mike McShane, who is replacing improv stalwart Jim Sweeney. Sweeney is, sadly, now too unwell with the multiple sclerosis he has suffered from since 1985 to carry on touring.

I wonder what, to Paul, is the main appeal of improvisational comedy?

“I compare it to the years when I did stand-up in the early to mid 80s,” he says. “Bits of it were fun, the bits on stage, but when I’m sitting in some dressing room backstage at half-time and hearing the buzz of hopefully excited people and I’m here on my own, I think, ‘Why am I here on my own?’

“Compared to that there are five people on this tour – we travel around on a coach with each show being different every night; that’s a key thing. If you get an idea that you think is a funny idea, you don’t have to pitch it, you just do it and find out there and then if it’s funny. Normally it is, but if it isn’t, then this person on stage with you will have a better idea and if they don’t, then this other person will and it’ll happen given time. This freedom to just come up with stuff and not have to take it to anybody or get a show of hands can be liberating.’

In the current climate of audiences wishing to be as much of a star as the genuinely famous (a cult which covers everything from X Factor auditioning to comedy club heckling), a regular avenue for the public to gain a vicarious sense of fame is via the improvised stage act and the potentially dreaded ‘audience suggestion’.

This allows members of the audience to offer scenerios for the improvisation to take place, such as a busy bar on a Friday night. Paul must have heard a few crackers in his time?

“The things that people write down in the dark under the cloak of anonymity can sometimes be quite scary,” he says. “We might look at something and think ‘we just can’t do that’. If you ever see someone pick up a card and say ‘I can’t do that one’, it’s almost always on the grounds of taste. They might be homophobic, say, or there was the one where within a month of the London Underground attacks, we had a card that said: ‘travel on the Underground with a rucksack stuffed with explosives’. Now, that’s just not going to work and if we tried it we’d end up being booed for someone else’s suggestion.”

Merton once told Melvyn Bragg that many people were unaware of his previous life as a stand-up comic and believed that he was “born to sit behind a desk and make quips about the week’s news”.

Anyone who still believes that clearly hasn’t seen him in his latest reincarnation as esteemed TV traveller, following in the footsteps of Michael Palin by heading off to very distant foreign soil accompanied by a camera crew and interpreters, being led on by an inquisitive eye and kept cheerful with a dry English wit.

For Five, Merton has visited China and soon he will be viewed in the follow-up, heading to India for a gruelling two-month stay. “From the crew’s point of view, we got better material than the China series, but it was an intensive thing and I reached a level of exhaustion where I was getting chest infections and a bad stomach,” he reveals. “Since I’ve been back, I’ve mainly just been lying around.”

Without putting too fine a point on it, did any of the Indian cuisine match up to the delicacies he savoured in China, such as the donkey penis? “Nothing can compare to that. They tried me on sheep’s brains fairly early on but some Indian food can be a bit ordinary and once in a while in a luxury hotel you find you’re going for something on the western menu or the Chinese menu to just have something different.”

Such programmes can only really work with a steady stream of oddballs and eccentrics falling into the presenter’s path. In India, Merton struck gold. “Inevitably your question leads me to BB Nayak, who holds the world record for receiving the highest consecutive kicks to his groin, which numbered 44,” he recalls. “He’d picked out five people to kick him 10 times each, but the fifth guy didn’t turn up. So we went down to see him and he asked me to kick him in the groin which I did with a steady rhythm; he congratulated me for my accuracy. Later that day, he established another world record at a local sports stadium by doing a series of cartwheels by using only the knuckles on one hand and he did 30 of those in a minute.”

Having passed his 50th birthday last year, Merton is showing little sign of slowing down. Once the Impro Chums tour cranks out its final ad lib at the end of June, he’ll be getting ready to direct and appear in a documentary for BBC4 about the British movies made by Alfred Hitchcock.

“Maybe I’ve changed physically, but I don’t feel any different. I feel 30,” he says. “But there were people I went to school with who when they were 16 were really 40 while there were people I worked with in the Tooting employment office like this 60-year-old guy who had the spirit of a 20-year-old, so it’s just how you feel really. There’s a Dave Allen line that says it’s better than the alternative. I’m still pleased to be working and doing it.” And while he has his last laugh of the interview, the nation prepares to chuckle at the improvisational genius of Paul Merton and his fantastic foursome.

------------------ |

|

| Back to top |

|

|

faceless

admin

Joined: 25 Apr 2006

|

Posted: Sun Aug 03, 2008 2:51 pm Post subject: Posted: Sun Aug 03, 2008 2:51 pm Post subject: |

|

|

|

|

picture by Brian Moody

Silent knight - Paul Merton interview

Paul Merton takes a break from quickfire repartee to champion silent comedy and set the record straight about his life, loves and 'madness'

picture by Brian Moody

Silent knight - Paul Merton interview

Paul Merton takes a break from quickfire repartee to champion silent comedy and set the record straight about his life, loves and 'madness'

3rd of August 2008

By Catherine Deveney

scotsman.com

PAUL MERTON is an intense kind of man. That's not, by the way, subliminal code for 'nutty comedian'. The star of Have I Got News for You and Room 101 has been dogged by the notion of the performing depressive who makes his audience roar with laughter then scurries back to his dressing-room for a quick glug of gin and largactyl and a moody contemplation of his razor blades. No, Merton's intensity is more a sense of passion, of focus, of really caring about the DNA of comedy. He's describing his Edinburgh festival show, in which he talks about silent comedians and shows film clips, and quite frankly for the first five minutes I'm thinking, who'd want to go and see a load of crackly old Keaton and Chaplin films and have some comedic anorak tell you about them? After ten, his enthusiasm is so uplifting that I'm thinking, hmm, I'd quite like to see that.

Charlie Chaplin emerging round a mountain pursued by a bear he's oblivious to. Buster Keaton standing stock still as the front of a house collapses, escaping injury because he's framed in the empty window space. (The house weighed three tons and Keaton had a mere inch and a half clearance.) Laurel and Hardy stuffing a goat under the bed in their lodgings. It's what happens, isn't it, says Merton, deadpan, when two men get followed by a goat. But it's not that silent film per se is wonderful. It's that the brilliance of the comedians transcends the limitations of silence. "It turns out to be something beautiful," says Merton. The actress Mary Pickford once said that the best silent films made the lack of sound seem like an artistic decision.

Merton first started getting other people interested in silent comedies when he was 15. He took a projector to Ireland, to his Auntie Nellie's house in Cork, and put up a sheet in her living-room. Then he invited a bunch of kids round for a show. Two days later they were back, demanding a re-run.

It's a bit ironic that a man whose own comedy seems so clearly rooted in verbal brilliance should be enthused by silent films. He talks incessantly and intently on his favourite subject, but perhaps there's another reason for that. He does rather give the impression that he's frightened to stop in case you actually ask him any questions. He is not, after all, a man who loves the press – or, as he so sardonically puts it, "I can promise you I have never opened my heart to the Daily Mail."

AS A BOY, growing up in Fulham, in south London, Merton used to read about the lives of famous comedians. He was fascinated by the idea of Keaton and Chaplin being on stage from the age of three or four years old. To a boy who lived in a council house and whose father was a tube driver, it seemed a glamorous kind of life. He imagined what it would be like to be Keaton, travelling round vaudeville in America, meeting the likes of Harry Houdini backstage and spending only one day a week at school. Lucky Buster.

Merton's parents have retired to Ireland and have his videos in their sitting-room. They don't say they're proud, but they don't need to. He knows. Both have a keen sense of humour, and his father used to go to see comedians perform, but no one in his family had a showbusiness background – unless you count his grandfather, who worked as a theatre electrician. But Merton was interested in comedy, in circus clowns in particular, from the age of three or four. He was an imaginative child, making his fingers into puppets, creating characters and voices for them.

But he was also shy. "It seems like a contradiction, but the shy person who is a performer actually does make sense, because in a way, when you're young and shy, making people laugh is a good way to make friends. It's an instant connection."

He remembers particularly that he used the school dinner queue to hone his comedy skills. "It seems an odd thought after all these years, but I do remember distinctly on my eighth birthday saying to myself, 'Well, I'm making the kids laugh at school at the moment, but when they're older – when they're nine – I'll have to keep making them laugh, so my jokes will have to get better.'" An intense kind of thought for a child, perhaps. "I was really thinking in those terms, addicted to the intoxicating power of laughter."

You can see the shy man still in Merton, the veneer of verbal dexterity pasted over a more diffident base. But he did have the daring to give up his first job, in the civil service, to become a comedian. Not that he saw it as bravery back then, and it certainly wasn't any great indication of self-belief. He was 19 and had no ties, and maybe the deciding factor was that when he joined the civil service he met a woman who'd been working there since before he was born. "I thought, 'No, I can't do that. I'm not going to be here for 20 years.' I wanted to avoid being 50 and saying, 'I could have given it a go myself, you know…'"

Merton was born in 1957, and being a comedian seemed a ridiculous aspiration. There were two options: touring working men's clubs or becoming a Redcoat at Butlins. "It was a completely different climate. What radically changed comedy in this country was the opening of the Comedy Store in 1979. The Comedy Store said anybody can get up and have a go. You didn't need an Equity card. You could get up on stage in front of a bunch of drunks and try stuff out."

He gave himself five years to make it. "It was a working-class thing, a five-year apprenticeship. It's a pick-up from being eight years old and saying, 'I've got to make them laugh next year.' It's the same person, isn't it? But I don't want to give the impression that when I left the civil service I was writing six hours a day, because I was quite lazy as well." He experimented, made mistakes, and towards the end of that period he started appearing on television. "I never had to make the decision of whether or not to give up. I don't think I would have, but, equally, I wanted to be successful. I didn't want to be just doing a circuit forever."

He smiles. He's giving away secrets now, but he had studied so much about showbusiness before he entered it that he knew success sometimes came from being good in a really bad show. He was given the perfect opportunity when offered the chance to do his polished stand-up routine in a show of rough sketches created by the public. How could he not shine by comparison? But the way he handled it explains the key to Merton's success. "It was an important gig, with the commissioning editors from Channel 4 watching the pilot, and I've always had the big-match temperament." He raises his game rather than crumbles? "Absolutely. Every time."

It's why he is so good at improvisation – and that's another link to those silent comedians, who financed their own films and therefore had artistic freedom. Improvisation is the last freedom for modern comedians – you have an idea and you do it. You don't have to get permission. "If I get a funny idea and everybody laughs, well, we didn't have to have a meeting about it. Nobody says, we can't afford it. Nobody says, it's been a tough year for the channel…"

Merton really gives a sense of knowing his own skills and strengths without displaying ego. Yet, as a performer, he wants to be seen by as many people as possible. "That's not really an ego thing…" He pauses. "Oh, I suppose it must be… but what I was going to say was, it doesn't bother me not being in front of the camera. In fact, I sort of prefer it. I'm not driven to be a performer… it's comedy in general… If I was given a strict choice between no more performing and successful directing, I'd go, 'yes…'"

He's directing a film about Alfred Hitchcock at the moment, and he loves being behind the camera. "You're in the texture of comedy, in the material. You think, 'Okay, if I put that shot with that shot that's going to make it funnier. And I can take that line of commentary out because the visuals are telling me that.' You're in the nitty-gritty of comedy, of shaping and forming. I absolutely love it."

In his early days as a performer, just when his career was taking off, he faced a difficult period that resulted in him being admitted to a psychiatric hospital. It's the basis of all the stories since about Merton the depressive, but the cuttings conflict a bit. What's the truth? "The truth is that some journalists can't resist the comedian who is also the tragic figure," says Merton. "What actually happened was that in 1990 I had gone to Kenya and had a severe reaction to an anti-malarial drug, which I think has since been taken off the market. I was hallucinating… no, hallucinating is too strong a word… but I remember sitting at home having got back from Kenya, and it was three in the morning and I was sitting in this armchair, just completely… I don't know, like I was full of caffeine or something… completely wired. My behaviour was strange, and people were getting worried."

He signed himself into the Maudsley hospital, staying for six weeks. "After a while you stop taking the anti-malarial thing. Nobody identified it at the time. It was when I came out that I saw a psychiatrist, a top guy." The psychiatrist investigated the drug and discovered that several other people had reacted badly to it. He pinned Merton's problems on the medication. He doesn't feel any embarrassment about the idea of mental illness. "It's nothing to be ashamed of. It can happen to anybody." But he didn't really feel it did happen to him in the way people think it did. It was all a long time ago, but Merton feels it has shaped attitudes to him since. He wanted a certificate from the Maudsley: 'Legally sane'.

He married the actress Caroline Quentin, but they broke up in 1997. He subsequently married Sarah Parkinson, a writer and producer. Tragically, Sarah developed breast cancer and died. Afterwards, Merton explains, journalists fixated on that long-ago spell in hospital. For example, he had once innocently told a story about being on a bus with Sarah at a time when he'd grown an unruly beard. Sarah told him he was looking a bit like a tramp and needed to smarten up. Oh, he was fine, Merton told her. But then a tramp got on the bus, took one look at Merton and offered him his can of beer.

It was a funny story – reminiscent of one of his beloved silent films, in fact – but it was taken out of context and referred to as if it had happened after Sarah's death, as if it was Merton losing the plot. "They tried to say I had a nervous breakdown after Sarah died, which wasn't true. A few weeks after she died, Have I Got News for You started and I was doing that. A couple of people said, 'Are you sure you want to do the show?' and I said, 'Well, I don't want to sit at home watching someone else doing it, to be honest.'"

Suddenly Merton realises he has been talking about Sarah without being asked about her. "I don't want to talk about Sarah," he adds, "but it was not a sudden death. It was not like a car crash, where someone is suddenly gone."

WE ARE in the middle of our own little silent sequence now. Words are failing. Chaplin once said that when he opened his mouth to talk he was just like any other comedian, but in mime he was sublime. It is true that silence can be revealing, throwing up other forms of communication.

There is, in this small room at Merton's agent's office in London, a subtle change of atmosphere. I have asked a follow-up question about Sarah, and it has changed everything. The enthusiasm, the connection that was created in the earlier part of our conversation, has dissolved, melting slowly like an ice cube into a puddle of uncomfortable embarrassment. And yet I admire the way Merton handles it. He tries to avoid being abrasive. In fact, there is something about his discomfort that draws me to him, makes me want to alleviate it, but my attempts are making it worse. There is a miserable kind of shifting in seats. An uneasy half-smile.

Before she died, Sarah wrote an article saying she believed her breast cancer had been triggered by the massive doses of hormones she'd received during IVF treatment. Did he share that belief? Pause. "Yes," he says finally. "Yeah, it seemed like it. She said what happened and when it happened, but I didn't want to get involved in trying to sue somebody or… but, yes, that's how it felt to us and how it felt to her, certainly."

Sarah opted for alternative therapies as well as conventional drugs, and refused chemotherapy. Had that worried him? The unease in the room is almost tangible now. Silence. An expression torn between discomfort and irritation and an appeal to my better nature. His words are so sparse that they're like the single line of dialogue on the silent film screen. "We're talking rather a lot about Sarah."

If it was up to him he might talk, but he doesn't want to upset Sarah's family, he says, which is probably a very understandable white lie. I really doubt Merton would want to talk anyway. Nor does he want to talk about any desire to be a father that might have prompted IVF. "I have never sold my story, done Hello! magazine, any of that stuff. I'm not guilty of exploiting my private life for cash and then saying, 'Oh, I don't want to talk about my private life.' I've never crossed that line."

Didn't he, after Sarah died, do a tabloid piece about his new relationship with partner Suki Webster? (Webster is a comedian who appears in the other show he's doing for the festival, Impro Chums. The relationship floundered for a while but is back on.) No. The paper snatched a picture in the street then ran a piece implying he'd been interviewed. But he hadn't. Things get manipulated. Which is why it's not what I do with this conversation that worries him – it's what someone else does afterwards with what I do. And there's really no answer to that.

But he does say he's happier in a partnership than alone. So let's talk more generally about the healing power of comedy, how it helped him move from the difficulties of his life – divorce and bereavement – to more positive phases. Most people find it very difficult to be upbeat when they are personally upset. How did he create comedy during turmoil? Laughter, he says thoughtfully, produces endorphins in the brain. It makes you feel good. "What I was doing, concentrating on comedy and doing Have I Got News for You, was an escape from grief, because we can only focus on one thing at a time. Well, certainly men can. We don't do multitasking. If you ask me to concentrate on that box of tissues on the table, the rest of the world disappears. So there's a sort of job satisfaction: you make people laugh."

After Sarah died, he went down to the Comedy Store every Sunday. "I wasn't going on stage at that point – I thought it might be misconstrued – but I wanted to go on stage because of the release. If you're improvising successfully, I'm listening exactly to what you are saying and my thoughts are with you and that's what your brain is full of. So, for the two hours you are doing the show, that's all there is. Then you come back from that and you're back to… It's not that you're forgetting, it's that you're getting an escape for a while."

Think of documentaries about very poor people. "They can be in very depressing situations but you often find laughter is a really powerful presence in their lives." There was even laughter in the concentration camps. He stops, apologises, says perhaps that's a crass example. Not at all. It's a powerful example of human instinct and resilience – an instinct Merton finds uplifting. "Someone like Bernard Manning, his comedy was about saying 'the reason your life is crap is because of these Pakistanis'. But it doesn't have to be about 'hate this', 'hate that'. It can be about beauty," he insists. It can be about the simplicity of seeing a film that is 90 years old and still funny.

Humour has been a support in his life. "When things are difficult, awful, stressful, the thing that always gets you through is a sense of humour. I don't mean – well, maybe I do – laugh at the hangman as he puts the noose around your neck. But an eye, an ear, for the ridiculous, the absurd in life, can get you through a lot."

Next year, Merton tours with Silent Clowns. He is looking forward to coming to Scotland because the show was so well received here in the past – particularly in Aberdeen, where 900 people turned up. The experience is not grainy old pictures on small monitors, but big screens and live music. It's about laughter and it's about life. "In the end, laughter and sex and having cigarettes are the only pleasures you can sometimes get." He pauses. "That's a bit of an exaggeration, but you know what I mean," he grins. "In the end, what else have you got?"

• Paul Merton's Silent Clowns is at the Filmhouse (0131 228 2688, www.filmhousecinema.com) from Friday until August 16, at 2pm; Impro Chums is at the Pleasance (www.edfringe.com), from Friday until August 23, at 4.30pm |

|

| Back to top |

|

|

faceless

admin

Joined: 25 Apr 2006

|

Posted: Mon Apr 06, 2009 4:53 pm Post subject: Posted: Mon Apr 06, 2009 4:53 pm Post subject: |

|

|

|

|

Paul on today's Paul O'Grady show (presented by Diarmid O'Leary) |

|

| Back to top |

|

|

faceless

admin

Joined: 25 Apr 2006

|

Posted: Fri Apr 23, 2010 12:57 am Post subject: Posted: Fri Apr 23, 2010 12:57 am Post subject: |

|

|

|

|

Paul Merton lands in Perth

Paul Merton lands in Perth

Apr 16 2010

Johnathon Menzies,

Perthshire Advertiser

RENOWNED comic Paul Merton will lead four other razor-sharp minds during a fully-improvised evening at Perth Concert Hall on May 3. The ‘Have I Got News For You’ regular will take to the stage alongside off-the-cuff experts Richard Vranch, Lee Simpson, Suki Webster and Mike McShane as part of their ‘Impro Chums’ tour.

Unscripted, but critically-acclaimed, Merton praised the flexibility of a format that requires no preparation whatsoever.

He laughed: “I haven’t written a joke for 25 years. We were in a bar in Edinburgh one year, 20 minutes before the show was due to begin. We wanted to write down the different verbal games we would be doing in the show, but realised we didn’t have a pen or paper. We had to borrow the waiter’s pen and notepad – that’s the great thing about doing this show – there’s no stress involved.

“We don’t have any scripts or props. I remember one comedian, Owen O’Neill, was astounded that – with absolutely no preparation – we were about to do a show in front of 1000 people. Planning doesn’t work because it throws the other performers, who might not know what you’ve planned. It sounds very difficult, and crazy, to go on-stage with nothing in mind, but that’s actually the show’s strength,” he said.

McShane, an American who became a star thanks to Channel Four’s ‘Whose Line Is It Anyway?’, cites 25 years of working in close proximity as the key to success.

He said: “We know how to play to each other’s strengths. Also, if it goes belly-up, someone will cover you. The show plays very fast and loose, and you know it’ll get a little crazy. But you’re always aware that it’ll never fall apart – someone will stick their neck out and help you.”

Webster, who co-wrote several documentaries presented by Merton, chips in: “The only skill you have to learn is, don’t plan and don’t worry. The key is simply listening and reacting to what the other person has just said.”

Producer Simpson, who also acts, reckons that, “audiences lap it up, because they can see we’re really enjoying ourselves – the enjoyment keeps it going. We love to muck about on stage. We take risks for fun, drop each other in it and mercilessly ridicule each other.”

Vranch, who also appeared on ‘Whose Line Is It Anyway?’, promised that their Perth performance will be unique. He said: “Audiences can see that the team is more important than the individual, I think they love the fact that it’s different every time. They know that a great scene involving, say, a nuclear bomb up the Eiffel Tower, isn’t going to happen again!”

‘Paul Merton’s Impro Chums’ is at Perth Concert Hall on May 3. |

|

| Back to top |

|

|

faceless

admin

Joined: 25 Apr 2006

|

Posted: Mon Apr 16, 2012 7:29 pm Post subject: Posted: Mon Apr 16, 2012 7:29 pm Post subject: |

|

|

|

|

The Big Interview: Paul Merton

The Big Interview: Paul Merton

Chris Bond

Yorkshire Post

16 April 2012

Paul Merton’s latest comedy show promises a little bit of everything. “There’s stand-up, sketches, music, magic, variety and dancing girls, although two of them aren’t in fact girls... how does that sound?” he asks. The 54 year-old comedian is speaking during a break from his latest comedy tour, Out Of My Head, which arrives in Yorkshire next month. For someone regarded as one of Britain’s most popular comedians, it’s surprising to learn that this is his first stand-up show he’s done in more than decade.

He has written it with fellow comic performers Lee Simpson and Richard Vranch along with his wife, Suki Webster, who all appear with him on stage. “The important thing is the show, it’s not important who comes up with the gag, it’s about whether it’s funny, it’s not about egos,” he says. “I like bouncing ideas off other people and I like seeing the audience’s reaction, so it’s going to be a journey of discovery.”

Merton is a fan of early music hall acts and the show doffs its cap to vaudeville, although he doubts he would have suited that life. “I’m not sure I could have survived back in the 1890s because a lot of the performers were raging alcoholics. Theatre managers were very keen on the public meeting the people they saw up on stage and the performers would go to the bar afterwards and people would buy them drinks all the time, so I would probably have picked up some bad habits.”

But he has clearly revelled in the process of putting together a show that is fully scripted. “Working on a tour that starts off as a mere jotting on the back of a fag packet and develops into a spectacular show is a sheer joy.” He has also enjoyed collaborating. “I’m different from some other comics I suppose. I’ve done plenty of solo shows over the years and it sounds a bit of a cliché but at the interval when you’re sat in your dressing room on your own, all you can hear is the buzz of people laughing at the bar, so you’re probably the most miserable person in the building. Also, I don’t like the sound of hearing my own voice for two hours.”

Merton grew up in London and was fascinated by comedy as a youngster. “I remember a kid at school telling me about this weird TV show he’d seen on Sunday night called Monty Python, although by then I was already a fan of the Goons and old school comedy like Max Miller, Charlie Chaplin and the Marx Brothers.”

Though he had harboured ambitions of becoming a comedian since his school days, it wasn’t until the early 80s that he started getting gigs on the cabaret circuit. “Back in the 50s, before the age of TV, you were expected to perform your routine whatever it was, you couldn’t deviate from that because it could get you the sack, you didn’t suddenly bring in a bit of juggling. I had a 17 minute routine and once I had enough jokes that worked, I kept them. I suppose it was the old way of doing things which was fine on stage but once you’re on TV you have to have new material.”

In 1985 he helped set up The Comedy Store Players, an improvisational troupe, whose recent members include Josie Lawrence, Phill Jupitus and Marcus Brigstocke, and he continues to join his fellow players as often as he can to hone his improvisation skills. “Doing The Comedy Store Players every Sunday means you’re match fit all the time. It’s a performance muscle. If it’s not getting flexed, it gets flabby. That’s why people who haven’t been on stage for a while struggle when they go back to the theatre because it’s a completely different discipline.”

Performing with the Players helped him perfect the off-the-cuff style of humour for which he’s become renowned. “You just ride the wave of laughter and then you might come up with something equally funny. Ralph Richardson used to talk about pushing a huge ball up a hill to the point where it suddenly gains momentum and starts rolling down the other side. That’s what live comedy is like. The only snag is, you have to do it while trying to look completely relaxed.”

In the late 80s, he made his TV breakthrough on Channel 4’s influential Whose Line Is It Anyway? along with the likes of Clive Anderson and Tony Slattery. But although he enjoys improvising on stage it has its downsides. “It can be exciting but I don’t remember the details afterwards which can be frustrating. I remember the audience laughing, but when you’re doing impro the brain makes decisions that you don’t need to remember and afterwards it’s like your head’s been wiped clean. Which is why I like the new show because you have lines to learn and they sink in.”

Since the early 90s, Merton has been in great demand both on the radio and TV. “When you start doing something you never think it will last but I’ve been extremely fortunate. With I’m Sorry I Haven’t a Clue I came in after it had been going for 20 years, so I was able to slot right in. But there’s something Jack Benny said in his autobiography that has stayed with me, he said ‘always work with talented people’ and he was right. If you have good people around you the show becomes better.”

The show which made him, and Ian Hislop, household names is the BBC’s hugely popular panel quiz show Have I Got News For You. It’s hard to believe the show, which has just started its 43rd series, has now been going for 22 years. “I’ve heard that some people who miss the news will actually watch Have I Got News For You to see what’s been happening that week,” he says.

So there’s no plan to call time on the show just yet? “If you get bored then the audience becomes bored, so as long as it stays fresh and me and Ian still enjoy it, then there’s no reason why it can’t keep going for another three weeks,” he says, laughing.

But he is, in all seriousness, delighted by the show’s enduring success, pointing out that the last Christmas special they did attracted 5.8 million viewers. So what is the show’s appeal? “I think the format with me and Ian seems to work and I try and treat each show as a one-off because that way I know I have to be as good as I can be, also I think having a different host has helped create a different vibe. It’s familiar yet different at the same time and there’s enough to keep people interested.”

He talks affectionately, too, about his fellow team captain. “Ian’s a very funny man although he doesn’t always get enough credit for it.” But as editor of Private Eye, Hislop has made a few enemies over the years, although as Merton points out none of them have been able to uncover anything scandalous. “He told me once that reporters had even phoned his priest to try and get something on him but they didn’t find anything. He’s unbearably squeaky clean but as editor of Private Eye he probably needs to be like that. There are some people who would like to say ‘what about the love child in Llandudno?’ But they can’t because there is no love child in Llandudno.”

Although he’s more than happy to continue doing the show, in recent years Merton has branched out with a series of TV documentaries on the early days of cinema and Hollywood, as well as carving out a successful career as a travel documentary presenter which has seen him visit places like India and China. But it is comedy that remains his true calling. “There’s no rule book, there’s nothing you can’t do as long as it’s funny and it’s entertaining, you don’t have to play safe,” he says.

“Years ago, I went to watch Dave Allen, it was just him telling jokes on his own for two hours with what looked like a glass of water and he was hilarious. He then started to tell this creepy story that had the audience hanging off his every word and you realised what a supreme storyteller he was. I came out afterwards feeling 10 feet tall, it was totally life-enhancing and that’s the kind of comedy I like, comedy that makes you feel a better person.” |

|

| Back to top |

|

|

|

|

|

|

You cannot post new topics in this forum

You cannot reply to topics in this forum

You cannot edit your posts in this forum

You cannot delete your posts in this forum

You cannot vote in polls in this forum

You can attach files in this forum

You can download files in this forum

|

Couchtripper - 2005-2015

|